Design for the mind: creating inclusive learning environments for all

Architecture and Design Scotland and Scottish Futures Trust (SFT) recently hosted a two-part shared learning event looking at learner experiences and design considerations for additional support for learning. These insightful sessions brought together over 295 attendees from Scotland to explore the critical connection between physical learning environments and the experiences of all learners, especially those with additional support for learning (ASL) needs and neurodiversity.

The overarching message from both events was clear: by designing with empathy and a deep understanding of diverse needs, we can create learning environments that are not just accessible but genuinely empowering for every child.

The imperative for change: Scotland's ASL Inquiry

The series began by addressing the Scottish Parliament's 2024 inquiry into Additional Support for Learning.This timely review of the 20-year-old ASL Scotland Act 2004 highlights the growing number of learners with more complex support needs and the urgent requirement for updated guidance.

A key finding of the inquiry was the often-negative experiences learners face due to their environment. Neurodivergent learners are particularly susceptible to factors such as acoustics, crowds, lighting, and smells. As the inquiry noted, "It is the architectural, sensory and social stimuli that create a barrier" to learning. This has led to a recommendation for new guidance, developed collaboratively with a wide range of stakeholders, including neurodivergent teachers, parents, learners, researchers, charities and architects.

Understanding neurodiversity and the built environment

Jennifer Stirling and Jean Hewitt of Buro Happold provided crucial context, emphasising that neurodiversity reflects the natural variation in neurocognitive profiles across the population – it's not a "one size fits all" world. They shed light on challenges such as outdated building guidelines, difficulties in adapting existing spaces and large class sizes.

A critical distinction was made between hypersensitivity (experiencing sensory overload, affecting 70% of diagnosed neurodivergent individuals) and hyposensitivity (seeking additional sensory input). This understanding is fundamental to designing accessible and inclusive learning environments.

A guide for designing for the mind

A central theme across both events was PAS 6463: Design for the Mind, a publicly available specification (PAS) or voluntary standard aimed at mainstream public and commercial buildings, with education at its core. This standard offers invaluable guidance for creating environments that minimise harm, particularly for individuals with hypersensitivities.

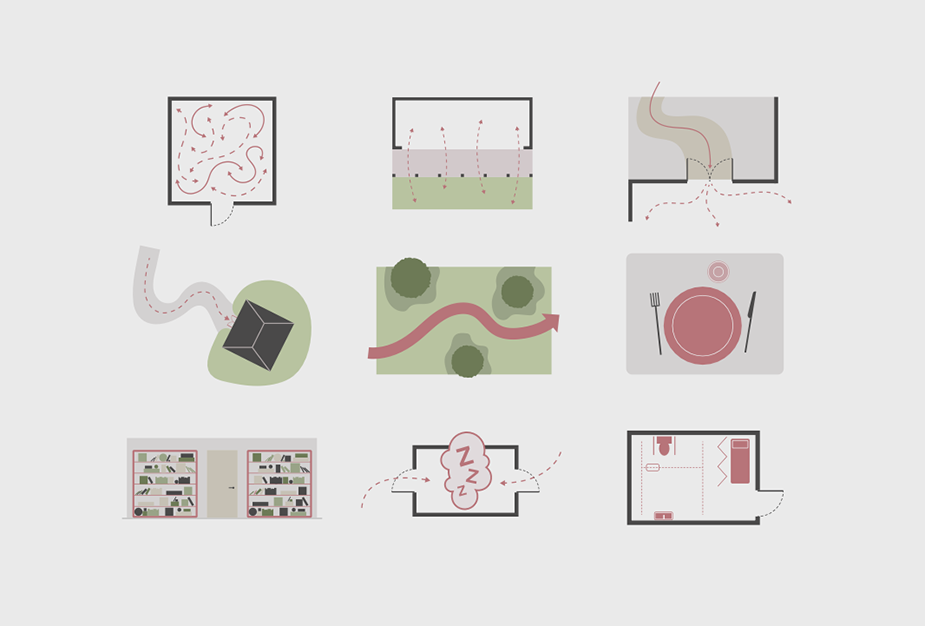

Jean Hewitt elaborated on key considerations from PAS 6463:

- site and building layout: avoiding confusing patterns, optimising sightlines, and incorporating nature can significantly reduce disorientation and dizziness.

- wayfinding: clear and intuitive navigation, including previews of layout changes and sensory mapping, empowers neurodivergent individuals to move through spaces confidently.

- external spaces: prioritising natural materials like wood and timber for their therapeutic qualities.

- internal layouts: offering varied learning opportunities, including spaces for movement and quieter, smaller group settings, where many neurodivergent children thrive.

- M&E (Mechanical & Electrical): addressing hypersensitivities to smells from cleaning products and materials (e.g., using plants like bamboo to remove formaldehyde).

- acoustics: thoughtful design, adjacencies, and zoning to manage sound variations.

- lighting: recognising the impact of flicker rates and the benefits of warmer, adjustable colour temperature lighting.

- surface finishes: opting for muted colours, avoiding intense patterns (especially stripes and Venetian blinds), and minimising "visual noise" that can trigger fatigue.

- low noise: specifying soft-close cupboards and low-noise hand dryers.

- safety and recovery: incorporating quiet, restorative spaces, even small ones, to allow individuals to decompress from overstimulating environments.

Buro Happold's "3 Cs" for inclusive learning environments resonated strongly, providing a framework for actionable design:

- clarity: providing advanced information, clear wayfinding, and logical, familiar, and easy-to-interpret spaces.

- choice: offering diverse spaces for different activities and neurocognitive profiles, allowing users to adjust to light or noise, and enabling avoidance of busy areas.

- calm: ensuring access to spaces for quiet, focus, and reset, including dedicated quiet rooms.

Inclusive design in practice: lived experiences and case studies

Fran Foreman from Education Scotland emphasised that inclusion is the cornerstone of achieving equity and excellence in Scottish education. She highlighted the importance of a child-centred, universal approach that reduces stigma, increases independence and is ultimately more cost-effective. Key considerations for architects and designers include promoting independence, dignity and rights through a multisensory approach, flexibility, wide sensory pathways, appropriate lifts and toilets, and careful consideration of technology and outdoor environments.

Maxine Booth from Aberdeenshire Council brought the discussion to life with powerful insights from Inverurie Community Campus. She shared an individual's lived experience of education with neurodiversity and presented a compelling video of students and teachers sharing their direct experiences, highlighting both successes and areas for improvement.

Our Principal Designer, Lesley Riddell Robertson, shared inclusive and accessible design principles through the lens of the Craighalbert Centre. This national centre for children with motor impairments aims to create a shared, integrated nursery environment designed as a showcase for mainstream nurseries striving for greater accessibility. The core message was clear: design must allow everyone to access what they want when they need it, being robust, agile, and adaptable. "The key is to create spaces that can be flexible and change with the users."

You can read more about designing for inclusive and accessible learning environments on our website here.

The path forward: towards a neurodiversity-informed future

Stephen Long from SFT highlighted the crucial need for designers to collaborate closely with the very people who use these spaces. Understanding diverse needs and sharing knowledge is paramount to informing truly effective design.

The commitment from the Scottish Government and SFT to develop new guidance by the end of this year is promising. An exciting announcement was made: a proposal to develop a dedicated "Design for the Mind School Supplement" document, with a steering group being established and the document being published for consultation by the end of 2025. This will be a significant step forward in translating these vital principles into practical guidance for school environments across Scotland.

These events truly highlight that by understanding how individuals experience the world differently, we can begin to design learning environments that truly enhance every learner's journey, fostering additional support for learning through thoughtful, neurodiversity-informed, and ultimately inclusive and accessible design.

About Learning Estate Investment Programme Shared Learning Events

Scottish Futures Trust, in collaboration with Architecture and Design Scotland, hosts and facilitates these events, fostering an open forum for discussing initiatives, sharing ideas, and addressing challenges within the learning estate.

To access the full report for this event or from previous shared learning events, please visit our dedicated webpage here.

Header image, spatial diagrams by Fraser/Livingstone Architects