Scotland’s Housing Expo took place in August 2010 – this blog written soon after the closure of the event reflects on the learning from the project and outlines specific design approaches to how the architecture of the place engages with the street.

With the gates now closed, visitors have returned to look again at their own homes, and the fanfare of a national event now passed, the real test for an experimental housing project in Inverness is only just beginning. Over the coming months 46 individually architect-designed houses and six apartments will be sold or leased, residents will move in and the innovations in architecture, urban design and renewable technology will be tested through occupation.

The Highland Housing Fair at Balvonie, Inverness; latterly re-named Scotland’s Housing Expo; will form a small community of 55 homes, containing a mix of private and social housing. With a full range of sizes and tenures, this is unlikely to become a ‘ghetto’ for the socially advantaged, contrary to local opinion. However, whilst physically linked with adjoining housing and nearby facilities of a school, sports hall and local shopping, it is inevitable that the new community of the Expo site will be seen to stand alone due to its distinctive architecture and urban form.

Two key facets of design

The design of the Expo housing has two key facets. On the one hand, there is the masterplanning and public realm design of the site, for which Cadell2 were responsible, working for the Highland Housing Alliance as the urban designer and author of a design code. On the other hand, there is the architecture of the housing, designed for 27 house plots, that responds to scenarios set by the masterplanning, exhibiting a diversity of solutions.

The brief for the 2007 design competition, the starting point for the architecture, started as a modest message about the search for a responsive site-specific architecture, designed for 21st century living and sensitive to the landscape of Highland Scotland. This was intended to inspire architects to participate. It became a rallying cry against the prevalence of the volume housebuilders’ standard product where this pays no heed to the local landscape, to street life or to notions of place and identity.

Original aspirations

In this article we review some of the original aspirations of the project, seeking to tease out some of the consequences of multiple designers working on a single site, the effect of the design code on the architecture, and the collective role of the many architects involved in creating a place with the capacity to become a community. We recap on the layout first then pick out three key themes of the project to illustrate the symbiotic link between urban design, conceived in an open-handed way, and the individual architecture of 50 realised homes and home-work units.

Site layout

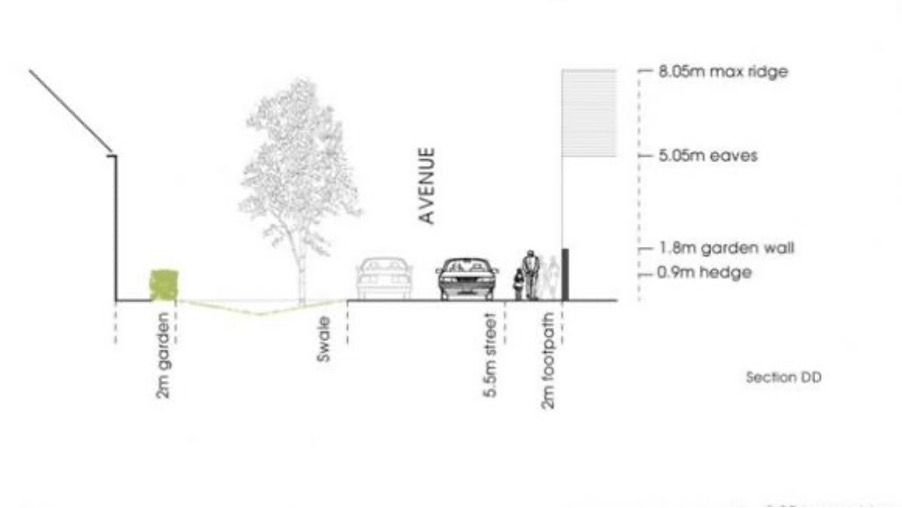

For those that do not know the site, the essential layout of the urban design is as follows; running down the hill, from south to north, are two principal routes: First the Avenue, with a parallel surface-water swale; in the middle is the Green, the focus of the public realm, at the hinge point between the two principal routes; then further down the site is the Brae, angled to reveal an expansive view of the Moray Firth. The Terrace and a series of lateral rural lanes, closes and courtyards are each laid out level, intersecting the principal routes and creating a network of accessible walking routes across the site and into neighbouring areas.

The principal routes have house frontages that combine to form street elevations. The lateral routes are defined more informally by side elevations and by garden walls, at a narrow six-metre width, frontage to frontage. These routes and related courtyards will contain public facilities for the community such as recycling areas and a location for small offices and studios.

Neighbourliness

The masterplan called for architecture that was joined with its neighbours into a common framework.

To achieve this a design code set down a variety of street types, with common characteristics such as eaves height, frontage line, depth of footprint and common material palettes.

Street characteristics

The architecture of each house had to interact closely with one or more of these sets of street characteristics. Some of the houses meet two or more streets, some architects consciously reflecting the complexities in the street environment to create a variety of elevations.

It was evident that some architects were more comfortable with designing in a close context than others. Some modes of architecture needed more space than others with some houses looking constrained by close-knit parts of the framework.

Sociability

The streets of the Expo are designed to reclaim the public realm for residents, our masterplan seeking better articulated streets with uses overlapped and mutually enriching instead of being segregated.

Shared space streets are designed throughout, as influenced by Hans Monderman and Jan Gehl, prioritising pedestrians, places for children to play and an extension to indoor living spaces. This will be evident as soon as you rumble over the rail sleeper bridge at the main road entrance. It has led to a rich pattern of paving material (some recycled from the streets of Inverness), kerb-free streets and deconstructed junctions. It requires close-knit architecture at key locations.

There are shared car parking spaces on the streets beneath the street trees. There are also shared refuse and recycling areas influenced by those at Staiths Southbank in Gateshead. The play space and the central green are integral to the street, as are street furniture for kids to play on such as a turf wall and sleeper bridges.

To complement this approach the masterplan called for an outward-looking architecture that would interact with public spaces and encourage street life. The street and public realm design invited a response in the architecture, calling for a consideration of indoor uses and opening positions that would support the various types of streets, lanes and public spaces. A starting point for all houses was to be close to the street and parking was laid out in such a way as to protect this proximity. All houses were to have front doors onto the street.

This met a mixed response from plot architects with some houses turning their backs on the street using small windows and inward-looking configurations or interiors focused on solar orientation alone. Others show a remarkable extrovert transparency to the street whilst preserving privacy in other ways. The key plot at the gateway into the site includes a surprise urban-scaled gesture in a large first-floor window.

A new vernacular

The masterplan sought a modern re-interpretation of traditional scales and formats of built form with some direction on palettes of cladding material and colours derived from indigenous rural buildings and the colours of nature. It sought a site-specific architecture responsive to topography and climate.

Elements of the infrastructure design, such as the access bridges over the swale, invited a response. Our intention was to provoke an exploration of the way in which architecture could address the materials, climate and topography of the site, an upland setting in the Highland landscape.

Diverse response

The response from architects is fascinating and diverse, but with many common points of reference. In terms of form the use of 1.5 storey and low two storeys, combined with a restriction on ridge height and plan depth, has led to a surprising intimacy of scale which can only really be appreciated on site. In terms of material there is a demonstration of a multiplicity of formats for the use of timber for cladding as screens and as solar shading, and some particularly interesting examples of the use of timber for roofing or as a homogenous, all-enveloping shingle.

Crinkly tin and plastic are also used with reference to agricultural buildings. There is a provocative use of black rubber that will ultimately be overcome by ivy, the building reverting to landscape and two houses are inspired by the patterns (petals) and vivid colours of nature.

The future

After a long gestation, the project came together astonishingly quickly in the end. Most houses were completed only within the immediate days or weeks before the public event. This was too close for comfort and with some rough edges showing, but enough at least for a remarkable, provocative and popular public event.

Although the central green and the play area are already in place, the paving, recycling stations, street-tree planting, and garden boundaries remain incomplete and the scope of the Architecture/Street correlation cannot be fully appreciated. Over the coming months, the remaining elements will be finalised and the houses occupied. We are looking forward to seeing how it is used and how the new resident community adjusts to the various innovations, and whether this becomes a different type of community; properly accommodating home working; more locally-based; lateral-thinking and with a community-oriented lifestyle.

All images: Cadell2

Find out more

Find out more about the Housing Expo project in the book, published by Architecture and Design Scotland and commissioned by the Scottish Government. It records the projects of Scotland’s Housing Expo 2010. The book builds on the achievements of the Expo and showcases the project to a wider audience.