The original house at Grishipol (rough bay) on the Hebridean Isle of Coll was built in the mid-1700s by Maclean of Coll for his Tac man or Factor.

It was the first lime-built square-cornered house on the island and took on the informal name The White House, distinguishing it from the basic black houses that were the norm on the island.

In 1773, Boswell and Johnson were entertained at the house whilst stormbound during their famous tour of Scotland. Fast forward to the 1800s the house was deserted as it had started to crack as it was built on sand.

In with the old and the new

Alex and Seonaid Maclean-Bristol acquired the building 150 years later. Some of the cracks in the roofless ruin were more than a foot wide, but the basic structure remained miraculously intact.

Alex was brought up on Coll and returned to farm on the island with wife Seonaid after spending some years away in the army. They were keen to create a house for their new family on the site, but the nature of the ruin presented a problem: should they restore it or build a new house nearby?

It was at this point that we suggested that neither of these approaches should be taken. The essential ruined nature of the structure was what gave it much of its magic.

So the idea of partial occupation of the ruin was explored with the intention that other new accommodation would be visually separate but physically connected to the ruin.

Preserving the original building

The original house had a commanding presence over the fertile dale leading to Grishipol Bay. Fingers of stone walls extended from the ruin forming garden-like enclosures.

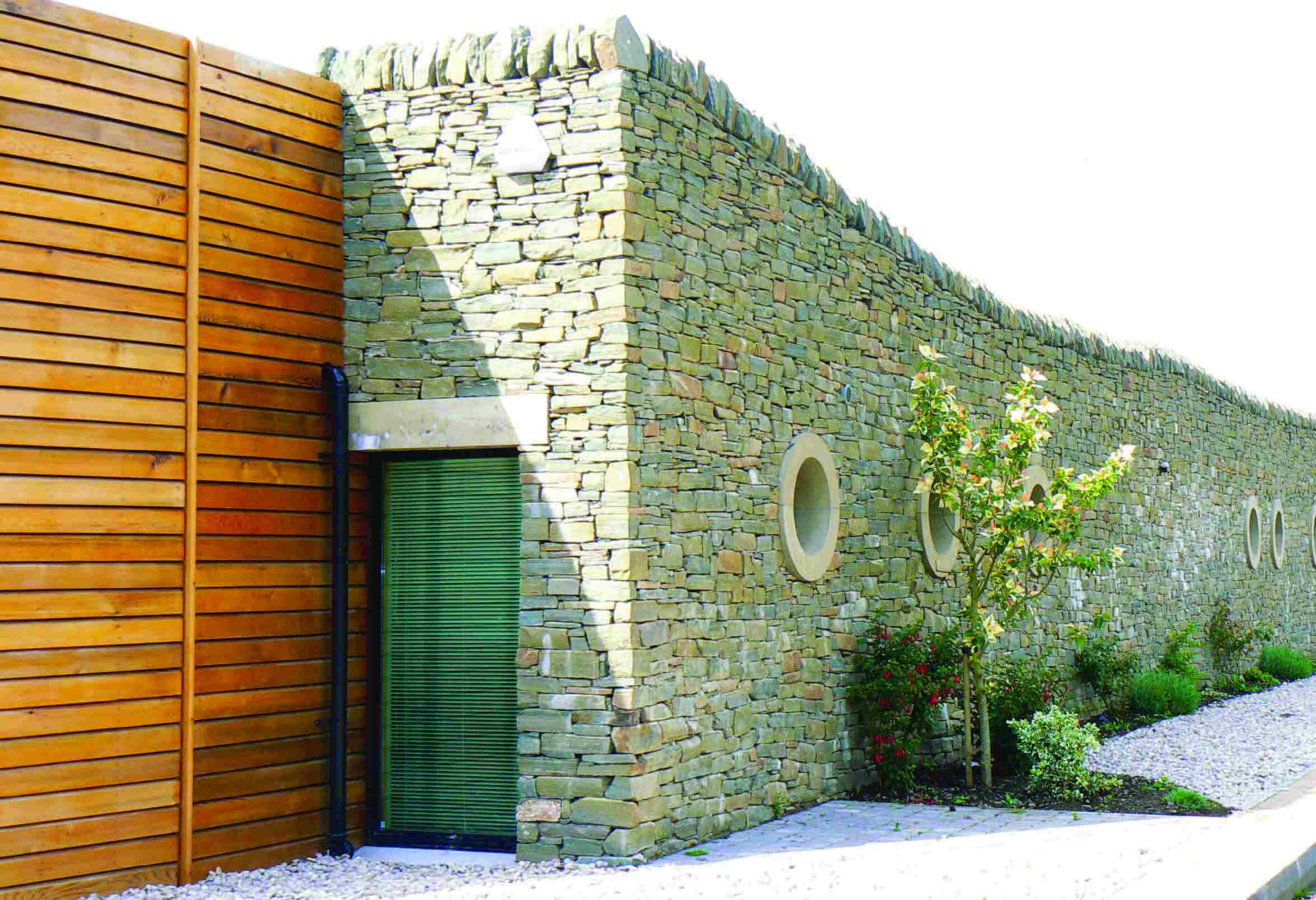

This led to responsive architectural forms for the new house where original tumble-down walls were built up and new enclosures constructed to create shelter, against which new accommodation could nestle.

This retained the tooth-like nature of the original building whilst breaking down the massing of the new structures and ensured that they remained subservient to the original building.

Almost half of the original house would remain roofless and become a courtyard garden, preserving the gutsy charm of the ruin.

The cracks on the building

Consolidation of the structure provided a challenge given the size of the cracks. And a system of exposed stainless steel ties and bracing frames in original window and fireplaces openings was devised with project engineers David Narro Associates.

There were no economic means of closing the main cracks up. It was also felt that they contributed so much to the identity of the house that they should be retained and enhanced where possible.

The consolidation work was carefully undertaken by local island builder Tom Davies, taking almost a year up to the point when the main construction contract started.

Spey Building and Joinery wins the contract

Sadly none of the island builders was big enough to take on the main construction phase of the build, so finding the right contractor led to a Scotland-wide search. Kingussie-based Spey Building and Joinery (SBJ) successfully won the contract.

This choice could not have been more successful with SBJ bringing all the skill and ingenuity of true Highlanders to the project.

Remote working led them to operate a two-week on/one week off schedule for the job. With only three ferries a week in winter, immaculate planning was needed. But the weather and particularity of the ferry service can often challenge the best-laid plans.

The site's remote setting led to the unusual situation of the client providing accommodation and catering in a nearby farmhouse throughout the build. This could have caused stresses and strains, but the positive attitude of both clients and builders alike meant this consolidated the team and helped ensure a smooth and happy build.

The result of the build

A three-storey high entrance hall and stairway was created in the main ruin, with half of it left as a roofless courtyard, following stabilisation and consolidation of the walls. A kitchen and master bedroom occupy the remainder of the original building with a tooth-like stack of stores, larder, WC, shower room and study at its core, all connected with a glass and steel stair.

To the rear of the original building, new living and bedroom spaces stretch out generously into the landscape with expanses of glazing to suck in the stunning landscape and sea views.

The new structures shelter between the new thick dry stone enclosure walls that pick up on and extend an original lattice of enclosure walls around the house.

Environmental considerations

An H-shaped plan provides pockets of external shelter on the very exposed site. The new stone walls include recycled rubble from the site, and imported aggregate and masonry were kept to a minimum to reduce transportation and environmental costs.

The building is heated through a heat exchanger powered by a wind turbine, meaning that on-aggregate power will be exported.

Materials of the build

The main hallway in the ruin connects to a living-dining room with glazed walls and a sedum-covered roof, the sedum echoing the natural flora on the site.

Slate paving stretches from the living room inside out to a south-facing courtyard on one side and a seaward-facing terrace on the other.

Calming and snug spaces

A wing of new rooms to the west provides four further bedrooms, utility spaces, and a panelled snug space, separated from the main living room by a wall of shelves.

Stairs wrap around this snug space up to a book-lined landing where a long window seat looks out over the big sheltering west wall and down to Alex's boat mooring.

Big open rooms are contrasted with smaller snugs, and nooks and crannies for an individual retreat, offering both expansive and intimate moments.

A house that works for its owners

Despite its high design ambitions, it remains a hard-wearing family farmhouse. Children bash their toys into the walls, and Highland cattle peer at their reflections in frameless glass walls.

It is a house intended to live up to the character of the ruin of the White House and engage and heighten the experience of living in an incredible place.

All images credit: Andrew Lee

Related case studies

Our website includes a wealth of examples and projects from across Scotland, and beyond. Visit the pages below for examples of related case studies.